Ruby Bradley

Contributors

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Adam Calhoun

- Lacey Dietz, RN, BSN

- Nicole Tirrell

- Chole Young

Reviewers

- .

Ruby Bradley

Ruby Bradley was born on December 19, 1907 in the small town of Spencer, West Virginia. Spencer, West Virginia is located in Roane County and is 50 miles (approximately 1 hour by car) northeast of West Virginia’s capital, Charleston. Spencer was founded in 1858 and originally known as “New California” until it was renamed after a Virginian jurist, Spencer Roane (“Spencer, West Virginia,” 2018). Spencer is in the Heartland region of West Virginia. This means that you will find some of West Virginia’s most defining characteristics such as farms, coal mines, rolling hills, oil and gas drills. The areas that were mined and then drilled for oil and gasoline never lasted long, leaving the majority of the region untouched. Today, the Heartland region consists of beautiful farmland, camps, and vacation properties (“Heartland Region,” 2018).

Born and raised in Spencer, West Virginia, Ruby was born to parents, Fred O. Bradley and Bertha Welch. Her mother, Bertha Jane Welch, was born on August 22, 1878 in Looneyville, WV and raised in Roane County, WV. When Bertha was 17 years old, she met 23-year-old, Frederick O. Bradley. They would go on to marry on June 21st, 1895. That same year the couple welcomed their first child, Jessie Carrie Bradley. In the coming twelve years, they would welcome five additional children: Doy Olive Bradley (1898), Smith F. Bradley (1900), Anna Hester Bradley (1902), Ruby Grace Bradley (1907), and Sallie Belle Bradley (1910), (West Virginia Pioneers, 2001-2020).

Ruby was the fifth of six children born into the Bradley family (Bullough, 2000). From a young age, she was taught to work hard. Her family owned a farm and it was here that Ruby participated in the daily work that accompanies the life of a farmer. Agriculture played a major role in the economy of West Virginia, which Ruby learned from a young age. Farming in West Virginia during this time period was a family affair and every member of the family had to do their part. The work required men, women, and children to assume many roles such as manual labor (Eagan, 1990). From an early age, Ruby understood the worth of manual labor and hard work.

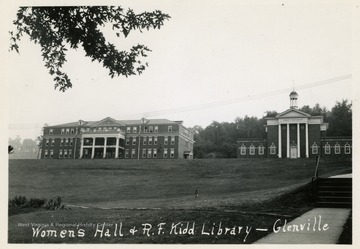

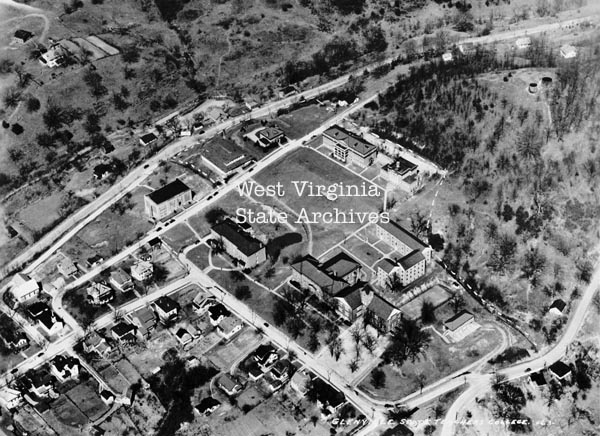

Her incredible work ethic motivated Ruby to pursue a degree in teaching and in the year of 1926, Ruby graduated from Glenville State Teachers College. Glenville State Teachers College has an interesting history. The citizens of Gilmer County, West Virginia longed for an educational system to be set up within the town. In 1873, a year after the state legislature approved a Glenville Branch of the West Virginia Normal School, 56 citizens donated funds after learning that no funds would be given. Within a few years of being established, those who had enrolled in the school exceeded the current population of Glenville. Later, the school earned the nickname the “Lighthouse on the Hill” for its quality of teaching and successful graduates. Glenville State Normal School became a four-year Bachelor of Arts school in 1930. On June 1st, 1931, the school became officially known as Glenville State Teachers College. (Glenville State College, 2020).

During Ruby's attendance at Glenville State College, tuition cost anywhere from $250 to $300 for an undergraduate degree. In addition to these primary costs, additional expenses were expected such as room and board, textbooks, etc. In the early 1900’s, the attending students were expected to pay approximately $400 for housing costs and approximately $30 for additional textbooks. This brought the total cost to an approximate $700-800 in expenditure each semester (Penn University Records Center, 2020). Despite these expenses, Ruby continued her education at Glenville State which would only be the beginning of her professional knowledge and experience. Eventually it would be used in teaching and educating young elementary aged children. In later years, her hard work would lead to an honorable nursing career, one that would be remembered by many for years to come.

Following her years at Glenville State Teachers College, Ruby returned to her hometown, Spencer, where she taught elementary-aged school children for four years in a one room schoolhouse in Roane county. Despite her love for children and teaching, Ruby had always been interested in the nursing profession. After seeing the diverse health concerns and desperate circumstances of those she taught, Ruby made the decision to enroll in the Philadelphia General Hospital School of Nursing in 1930 (Bullough, 2000).

The Philadelphia General Hospital’s School of Nursing brought a new level of professionalism to nursing. Originally founded as the Philadelphia Almshouse (also known as poorhouse) in 1731, the hospital school of nursing was meant to serve the mentally ill and the indigent. The school was formerly built in the center of the city, but eventually moved to a larger campus called “Blockley Township” and was known as the Blockley Almshouse until 1902. It was eventually renamed the Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). Today, this part of campus is now the University City section of West Philadelphia. During its time in 1831, the “Old Blockley” area was famously known for being overpopulated and filthy, leading the area’s people to a reform in the 1880’s in the hopes of restoring the town’s reputation. One of these reforms was led and established by Alice Fisher, a nurse who worked at the Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH) School of Nursing. Prior to working at PGH, Alice Fisher had been formerly trained by the infamous Florence Nightingale (Jakucs, n.d.).

In 1920, several decades later, the mentally ill and indigent patients at PGH were moved to Byberry State Hospital. The Philadelphia General Hospital School of Nursing then transitioned to operate as a modern, more conventional hospital. Despite its transition to a more modern, conventional hospital, staff continued to serve the poor and impoverished community honoring its roots as an almshouse. PGH also focused primarily on clinical and surgical services, which were apparently deficient until progressive mayors in the area fostered these resources. Eventually it became the number one hospital of choice for the African American population, particularly African American women. In 1977, the hospital closed decades later due to the establishment of additional healthcare facilities in West Philadelphia. The land was later claimed by the PGH Development Corporation and was named the Philadelphia Center for Healthcare Sciences, establishing seven medical research and treatment buildings (Jakucs, n.d.).

Ruby graduated from Philadelphia General Hospital School (PGH) of Nursing a few years later in 1933 with a specialty in surgical nursing (Jakucs, n.d.). Ruby’s time as a nurse in the 1930's was much different from today. There were many controversies in the medical field, especially in women’s health. During this time birth control was unavailable. In fact, the administration of birth control was illegal, and nurses were arrested for suggesting women to control when and how they had children. A substantial number of women were dying in childbirth or through giving self-abortions. It was also during this time that many children were suffering due to the inability of families to pay and take care of their children's health. This created a lot of responsibility on nurses, placing a great deal of pressure to follow the law regarding women's health and contraceptives (The 1930s Medicine and Health: Topics in the News | Encyclopedia.Com, 2019).

It was during the 1930’s while Ruby was a nurse that nurses began to specialize in different medical topics. Many different health needs were springing up, so nurses started to dive into specific areas of health. Topics such as anesthetics, surgery, and women’s health were some of the specialties that nurses started to gravitate towards. Anesthetics nurses became crucial due to the emergence of new anesthetics and methods to keep patients unconscious during surgery. Surgical nurses were more valued in the operating room and were being seen as assets to the physicians and the surgeries that were being performed. Women’s health nurses started to fight for women's rights and became expert activists on why women needed better health options. The 1930’s were important for nurses and their progression in the medical field (The 1930s Medicine and Health: Topics in the News | Encyclopedia.Com, 2019).

Another important note about nursing during the 1930’s was that healthcare was considered expensive. It was not something that everyone could afford. The minimum wage in the 1930’s was forty cents per hour which amounted to $800 a year. The chart below lists what some of the healthcare costs were in the 1930’s:

Measles: $4.81

Chicken Pox: $1.82

Whooping Cough: $6.27

Broken Limb: $18.07

Childbirth: $98.74

Heart Disease: $49.56

Pneumonia: $58.72

Although these costs are considerably less expensive than the costs of healthcare today, compared to wages these were not considered “cheap” services. During this time, health care and medical treatment was seen as more of luxury than a right. Due to health care being so costly, many individuals would not seek health care and treatment from a hospital setting but would try to manage health with their own resources. However, it was in the 1930’s that the idea of health insurance began to arise and supportive funding for individuals started to gain traction (The 1930s Medicine and Health: Topics in the News | Encyclopedia.Com, 2019). These are just some examples of what the nursing world was like when Ruby was entering the field. It paints an interesting picture of some of the experiences Ruby would likely have as a surgical nurse during this time.

Following Ruby’s graduation in 1933, the Great Depression was in full swing and jobs were difficult to come by, especially in rustic towns such as Roane county. Due to these difficult times and trying circumstances, Ruby was driven into the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and became a civilian staff nurse at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. (Bullough, 2000).

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) operated between 1933 to 1942. This was one of the earliest New Deal programs created to alleviate unemployment during the Great Depression and to administer national conservation work primarily for young unmarried men. The CCC provided projects for unemployed men which included planting trees, building flood barriers, fighting forest fires, and maintaining forest roads and trails (Augustyn, 2019). It was an honor for Ruby to be a member of this group and operation, one that would lead to even greater, more distinguished opportunities and positions.

Walter Reed General Hospital opened on May 1, 1909. Its origin can be traced back to Major William C. Borden and Major Walter Reed. Borden and Reed became friends while teaching together at the Army Medical School. While there, Reed became best known as the leading researcher to discover that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes. However, one short year after Walter Reed’s return trip from Cuba, he died from peritonitis following an appendectomy performed by his dear friend, Major Borden. After Walter’s death, Borden was dedicated to seeing the completion of the new hospital which would co-locate the Army hospital, the Army Medical School, the Army Medical Museum, and the Surgeon General’s Library. Borden was instrumental in naming the new hospital after his friend, Major Walter Reed. General John J. Pershing signed the order creating the Army medical Center on the same campus as Walter Reed General Hospital in 1923. World War l saw the hospital’s capacity grow from 80 patient beds to 2,500 in a matter of months. Through World War ll, Korea and Vietnam, the facility treated hundreds of thousands of injured American soldiers. (Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 2020). One such individual that took part in these hundreds of thousands of treatments was Ruby Bradley.

In 1934, Ruby joined the Army Nurse Corps as a surgical nurse and there continued her work at Walter Reed Hospital for six years. The United States Army Nurse Corps (AN or ANC) had been previously established by the US Congress in 1901. Today, there are six medical special branches or “corps” of officers which, along with medical enlisted soldiers, comprise the Army Medical Department. The ANC was a proud member of one of the six.

The ANC is the nursing service for the US Army and supports the Department of Defense medical plans. The ANC is composed entirely of registered nurses and its mission is “To provide responsive, innovative, and evidence-based nursing care integrated on the Army Medicine Team to enhance readiness, preserve life and function, and promote health and wellness for all those entrusted to our care. Preserving the strength of our Nation by providing trusted and highly compassionate care to the most precious members of our military family - each Patient” (Wikipedia, 2020).

While pursuing her work at Walter Reed Hospital, Ruby received her first overseas assignment from the ANC and reported to the Station Hospital at Fort Mills located in the Philippines on February 14th, 1940. She was transferred to Camp John Hay in Baguio, another island located in the Philippines on December 7th, 1941 (Bullough, 2000).

John Hay Air Station was established on October 25, 1903 after President Theodore Roosevelt signed an executive order setting aside land in Benguet for a military reservation under the United States Army. The reservation was named after Roosevelt's Secretary of State, John Milton Hay. For a time, elements of the 1st Battalion of the Philippine Division's 43rd Infantry Regiment (PS) were stationed here. Prior to World War II, a number of buildings had been constructed on base, including a US Army Hospital and the summer residence of the Governor-General of the Philippines, later to be known as The American Residence, which is now used as the summer house of the United States Ambassador to the Philippines (John, 2020). Camp John Hay was located on Luzon, a beautiful island 200 miles from Manila. Today, Luzon is the largest and most important island of the Philippines (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020).

When she arrived at Camp John Hay, Ruby was only 34 years old and quickly became an administrator for one of the hospitals. On December 23, 1941 the army evacuated Camp John Hay due to the bombing and invasion of Japanese troops. It was the first place in the Philippines bombed by Japan in World War II. At 8:19 a.m. on December 8, 1941 – December 7 on the Hawaii side of the International Date Line – seventeen Japanese bombers attacked Camp John Hay killing eleven American and Filipino soldiers, in addition to several civilians in the town of Baguio. (John, 2020). Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Imperial forces had also invaded the Philippines, dropping 70 bombs in the area of Camp John Hay. Over the next three weeks, American and Filipino troops fought valiantly against overwhelming Japanese forces but were eventually forced to retreat. In the chaos and destruction of the invasion, Bradley and thousands of other Americans were captured. (Forney, n.d.)

Ruby survived the attacks but did not make a full escape. She, in addition to an onsite nurse and doctor, hid within the hills just outside of the camp. They hid there for five days until they were betrayed by the couple that was assisting in their hiding. Due to unfortunate circumstances, Ruby and her two colleagues were captured by Japanese forces and sent to their former military post that had since become a prisoner of war (POW) camp.

A “Prisoner of war (POW), [is] any person captured or interned by a belligerent power during war...The captive, whether or not an active belligerent, was completely at the mercy of his captor, and if the prisoner survived the battlefield, his existence was dependent upon such factors as the availability of food and his usefulness to his captor. If permitted to live, the prisoner was considered by his captor to be merely a piece of movable property, a chattel...During World War II millions of persons were taken prisoner under widely varying circumstances and experienced treatment that ranged from excellent to barbaric.” (The, “Prisoner of War, 2018). One of these millions of people was Ruby.

While at the camp, Ruby continued to function as a nurse and did what she could to help the people around her. She and an onsite doctor created a care clinic within the prisoner camp. Together, they took great risks smuggling supplies such as medications and medical instruments from the camp’s hospital. The Japanese troops were unaware of the smuggled supplies and were surprised to learn of the treatment offered by Ruby and the doctor despite little to no resources on hand. The Japanese never discovered that they had obtained the supplies by breaking into what used to be one of their hospitals until it was overtaken by the Japanese.

During her captivity of 37 months, Ruby delivered 13 babies and participated in 230+ operations, a true sign of her allegiance and character to her calling as a nurse during such uncertain times (McLELLAN, 2019). For [those] 37 months, Bradley, along with 76 other nurses (65 from the Army and 11 from the Navy) witnessed unimaginable horrors. People starved to death, died from disease, and simply lost the will to live. The 35-year-old nurse’s weight dropped to a dangerously low 84 pounds, and she was always hungry and tired. But she never gave up. “I knew I’d get through,” she said in an NBC news interview. “I was sure of it.” It was during this time that Bradley and other nurses at the POW camps became known as “Angels in Fatigues” or “Angels of Bataan.” Although exhausted and malnourished, the nurses administered medical treatment and care to hundreds of captured Americans, many of whom were civilians. Despite Bradley’s best efforts, many of the captured Americans didn’t survive. "A lot of people died in the last few months," she remembered. "There were several deaths a day, mostly the older ones, who just couldn't take it." (Forney, n.d.)

In September of 1943 Ruby was transferred away from Camp John Hay to a remote camp called the Santo Tomas Internment Camp, located in Manila. The Santo Tomas Camp was a former university where the Japanese held captured prisoners such as stranded businessmen, housewives, and school children. The camp was 50 acres of fenced-in land. Altogether there were approximately 4,000 allied civilian POWs held captive in the Santo Tomas Internment Camp. Of those that died as prisoners of war during WWII were interned by the Japanese military, primarily from internment camps located in the Philippines. According to research, approximately 1,500 American civilians died from Japanese internment due to harsh treatment during captivity (Manila Liberation Reunion, n.d.)

The Santo Tomas Internment Camp is one example of such harsh and inhumane treatment, one in which Ruby was well acquainted with during her imprisonment. For example, Individuals were forced to separate by gender and placed in cramped classrooms for sleeping arrangements. They typically packed these small rooms with 30 to 50 people at a time. At any one time, there was approximately 1,200 men that occupied the main building with only 13 toilets and 12 showers in use (Kenny Burgess, 2015). These close quarters and lack of accessible hygienic sources led to the spread of disease within the camp. In turn, this led to several deaths per day, most of which were the older prisoners of war.

Upon her arrival to the camp, Ruby and several of the other incarcerated nurses established a clinic to assist in the well-being of the prisoners. The military and civilian captives named Ruby and the other nurses the “Angels in Fatigues” due to their amazing medical treatment and angelic care (McLELLAN, 2002). In addition to the challenges already mentioned, there were many additional struggles that Ruby and the medical staff encountered. Often, medical supplies were in very short supply leaving the Army nurses to use hemp for sutures, which had to be carefully autoclaved. Surgical supplies were almost completely non-existent and food availability was scarce. As a result, malnutrition became a problem (Army Nurse Corps, 2020).

The POW’s were mainly given rice for nutrition (half a cup in the morning and half a cup at night), making mornings and evenings a sought-after time of day for the prisoners. Male internees lost an average of 24kg (~53 pounds) during the 37 months of their internment at Santo Tomas (US Army Signal Corps, 2011). Despite the extreme shortage of food, Ruby often saved part of her rations for the children that needed it later in the day, thus sacrificing her own health and nutritional wellbeing. She also stole food and filled her pockets giving it to children and those in need.

During her three-year imprisonment, she helped with 230 major surgeries and the delivery of 13 babies. Although many nurses, including Ruby, did their best to save their fellow Americans, many did not survive. Ruby recalled, “A lot of people died in the last few months. There were several deaths a day, mostly the older ones, who just could not take it” (McLELLAN, 2002). When the camp was liberated on February 3, 1945, Ruby was only 84 pounds, approximately 20 pounds less from the 110 pounds that she was before her incarceration at Camp Santo Tomas (McLELLAN, 2002). These experiences, along with others, are just a few examples of Ruby’s honorable life and mission as a nurse during such tragic times. On December 25th, 1944 allied planes dropped leaflets assuring that the end of imprisonment was near. Shortly after on February 3rd, 1945, American Troops pulled up in war tanks to Camp Santo Tomas leading to freedom and liberation of those that had been imprisoned for so long (Kragen, 2016).

After the liberation of Camp Santos Tomas in 1945, Ruby returned home to West Virginia where she was given the Bronze Star and promoted to First Lieutenant because of her heroism and selflessness in the war. She remained in the United States for five years serving in the Army as the Principal Chief Nurse in Fort Eustis, Virginia Nurse Supervisor at Letterman General Hospital in San Francisco, California, and as Head Nurse at Banana River Naval Air Station in Cocoa, Florida (Army Nurse Corps, 2020).

In June 1950, North Korea crossed into South Korea marking the beginning of the Korean War. At this time, Ruby was promoted to Major and reassigned to Chief Nurse for the Eighth Army’s 171st Evacuation Hospital in South Korea (JAKUCS, 2020). It was in these evacuation hospitals where she served on the front lines and sacrificed herself yet again. At one point during the war, she refused to retreat unless she was allowed to load with the sick and wounded caused by Chinese snipers. She stayed in the position of Chief Nurse until 1953.

Along with hundreds of US Army, Navy, and Air Force nurses who served on hospital ships and MEDEVAC aircraft and with Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) Units, the field hospitals made popular by the 1970s comedy-drama TV series M*A*S*H, Bradley distinguished herself as a fearless combat nurse. In one harrowing incident, thousands of Chinese soldiers attacked a US Army position. Within minutes they had surrounded an airstrip where wounded soldiers were being evacuated. “Everything was happening so fast,” Bradley said in an interview in 2000. With enemy small arms fire and mortar rounds erupting all around her, she organized the evacuation of her patients, and in total disregard for her own life, helped load the wounded men into waiting planes. After ensuring everyone was safely aboard, Bradley jumped on the last plane just as her ambulance burst into flames. “You can get out in a hurry when someone’s behind you with a gun,” she told NBC news. Miraculously, Bradley survived the attack. When she returned to the States in 1953, her hometown honored her with a parade. (Forney, n.d.)

As she left Korea to return home from the army in 1953, she was saluted with a full-dress honor guard ceremony, making her the first woman to receive this kind of salute. The full-dress honor guard salute is one of the highest and respected actions an individual can receive. It is a sign of the utmost respect for the individual receiving the salute. The honor guard is still put into practice today. Honor guards today typically escort or welcome the President of the United States, participate in veterans’ funerals, or guard national monuments. The salute consists of anywhere from 10 to 100 soldiers that hold a salute in full uniform to the individual. The soldiers have a stoic look and show their respect for their individual (Long, 2019).

Ruby continued to ascend as a decorated nurse in the US army: “Col Bradley served as Chief of the Nursing Division with Headquarters 3rd Army at Fort McPherson, Georgia, from August 1953 to June 1958, and then as Chief Nurse with Headquarters U.S. Army Europe in Heidelberg, West Germany, from July 1958 to April 1961. Her final assignment was as Director of Nursing Activities at Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, from June 1961 until her retirement from the Army on April 1, 1963” (“Veteran Tributes,” n.d.). The US army turned out to be Ruby’s chosen calling in life and her dedicated, unending service will be honored and yearned by many for years to come.

Ruby Bradley returned to her small town of Spencer, West Virginia after retiring from the army. However, she continued to work as a civilian nurse for a private duty nursing service in Roane County, West Virginia. She was a supervisor for this private nursing facility from 1963 to 1980 (Matthews, 2012).

Her recognition for her efforts in WWII and the Korean War did not end with her retirement from the army or nursing. In September of 1991, the community of Spencer West Virginia came together and celebrated “Ruby Bradley Day.” The town put on a parade and other honorable ceremonies to show their gratitude towards Ruby and her service (Why Colonel Ruby Bradley Was Known as the Angel in Fatigues - Medals, 2019).

In her last years of life Ruby lived in a nursing home in Hazard, Kentucky. On May 28, 2002 she suffered a heart attack and passed away. She was remembered and celebrated as one of the “forgotten heroes of the military” (Wikipedia, 2019). Ruby’s funeral service was nothing short of honorable. She was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery which overlooks the nation's capital. “Her coffin was escorted to the grave site by six white horses, and the symbolic riderless horse followed, while the Army Band played traditional Hymns. A firing party of seven shounded three volleys in her honor, and the flag covering her coffin was presented to a relative” (Ruby Bradley (1907): Person, Pictures and Information - Fold3.Com, 2012). Many family members and Army soldiers paid their respects by placing roses on top of the coffin and also saluting her resting place as they left. Her life and mission will be commemorated for years to come and stand as a testimony of the duties that nurses must uphold to their country and to the world.

Today, Ruby Bradley is known as the most decorated woman in US history. Altogether, she earned a total of 34 medals and citations of bravery, two Legion of Merit medals, two Bronze Stars, a U.N. Korean Service Medal with seven battle stars, two Presidential Emblems, the World War II Victory Medal and the U.N. Service Medal, and the Florence Nightingale medal from the International Red Cross (Matthews, 2012). Her military ranks included: 2nd Lieutenant, 1st Lieutenant, Captain, Lieutenant Colonel, and Colonel. Ruby was promoted to the rank of colonel in 1958. She was the third woman in army history to be promoted to colonel. Colonel is the highest field-grade officer ranking. Many women did not serve in such prestigious positions during her time. It was a great honor, and many respected her and looked to her for direction (Colonel | Military Rank, n.d.).

References

- Augustyn, A., & The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2019, November 20). Civilian Conservation Corps. Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Civilian-Conservation-Corps

- Bullough, V. (2000). American Nursing: A Biographical Dictionary: Volume 3, Volume 3. Retrieved May 20, 2020, from https://books.google.com/books?id=KDWiFMNlOfIC&pg=PA24&lpg=PA24&dq=ruby+grace+bradley+early+life&source=bl&ots=-hP3QysYMM&sig=ACfU3U32WkSpZyuTA-gPfNoCcVBY0XbpjQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjFhYjAusPpAhWNVs0KHX0DBSM4ChDoATABegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=ruby%20grace%20bradley%20early%20life&f=false

- Colonel | military rank. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/colonel

- Eagan, S. C. (1990). “Women’s Work, Never Done”: West Virginia Farm Women, 1880s-1920s. Www.Wvculture.Org. http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh49-3.html

- File:Liberation-Men-- santo tomas.jpg. (2017, May 21). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 20:21, August 4, 2020 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Liberation-Men--_santo_tomas.jpg&oldid=244830381.

- Forney, N. (n.d.). An Angel in Fatigues. Retrieved August 06, 2020, from https://nedforney.com/index.php/2019/05/09/ruby-bradley-army-nurse-ww2-korea/

- Glenville State College. (2020). A Brief History of Glenville State College. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.glenville.edu/library/archives/history Heartland Region. (2018, June 16). Retrieved from https://wvexplorer.com/communities/regions/heartland-region/

- Jakucs, C. (n.d.). Col. Ruby Bradley, U.S. Army Nurse (1907-2002). Retrieved May 20, 2020, from https://www.workingnurse.com/articles/Col-Ruby-Bradley-U-S-Army-Nurse-1907-2002

- “John Hay Air Station” Wikipedia, Wikipedia Foundation, 7 May 2020 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hay_Air_Station#:~:text=World%20War%20II,-Further%20information%3A%20Battle&text=Camp%20John%20Hay%20was%20the,Japan%20in%20World%20War%20II.&text=The%20Japanese%20pleaded%20with%20Horan,from%20the%20advancing%20Japanese%20invaders.

- Kenny Burgess (2015, July 26). Santo Tomás Internment Camp, Luzon. Retrieved from http://philippineinternment.com/?page_id=11

- Kragen, Pan (2019, December 4). Internee has different memories of war. The San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/communities/north-county/sd-no-jim-crosby-20161128-story.html

- Libraries, W. (n.d.). West Virginia History OnView. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwvhistoryonview.org%2F%3Ff%255Bcorporate_names_sim%255D%255B%255D%3DGlenville%2BState%2BCollege.%26sort%3Didentifier_ssi%2Bdesc&psig=AOvVaw2JyVmKbl11KaQt_xWlroV2&ust=1590686465712000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAIQjRxqFwoTCIDsvILH1OkCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

- Long, P. (2019, November 20). The Prestigious Military Honor Guards. The Balance Careers. https://www.thebalancecareers.com/military-honor-guards-3343834

- Manila Liberation Reunion (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.us-japandialogueonpows.org/Manila%20liberation%20reunion.htm

- Matthews, D. (2012, October 26). e-WV | Ruby Bradley. Retrieved from https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/639

- McLELLAN, D. (2002, June 2). Ruby Bradley, 94; Army Nurse Was “Angel in Fatigues” for POWs. Los Angeles Times; Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-jun-02-me-bradley2-story.html

- McLELLAN, D. (2019, March 2). Ruby Bradley, 94; Army Nurse Was “Angel in Fatigues” for POWs. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-jun-02-me-bradley2-story.html

- Penn University Records Center. (2020). Tuition and Other Educational Costs: 1920-1929. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/tuition/tuition-1920-1929

- Philadelphia General Hospital Nursing Class. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, 2020, philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/nursing/professional-adjustments-class-for-senior-students-c1949-philadelphia-general-hospital-collection/.

- Ruby Bradley, Colonel, United States Army. (2002, July 3). Http://Www.Arlingtoncemetery.Net/Rbradley.Htm. http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/rbradley.htm

- Ruby Bradley (1907): Person, pictures and information - Fold3.com. (2012, May 3). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/page/527719039-ruby-bradley-1907

- Spencer, West Virginia (WV 25276) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders. (n.d.). Citydata.Com. http://www.city-data.com/city/Spencer-West-Virginia.html#:%7E:text=7%20residents%20are%20foreign%20born

- Spencer, West Virginia. (2018, June 16). Retrieved from https://wvexplorer.com/communities/cities-towns/spencer-west-virginia/

- Spencer West Virginia Hospital. (n.d.). [Photograph]. Pinterest. https://i.pinimg.com/564x/50/a1/5f/50a15f09ba7bd097fae644a089befa1a.jpg

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Luzon | Location, Physical Features, & Economy | Britannica. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Luzon

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Prisoner of War.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 11 Dec. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/prisoner-of-war.

- The 1930s Medicine and Health: Topics in the News | Encyclopedia.com. (2019). Encyclopedia.Com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/culture-magazines/1930s-medicine-and-health-topics-news

- Veteran Tributes. (n.d.). Retrieved July 6, 2020, from http://veterantributes.org/TributeDetail.php?recordID=1206

- Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. (2020, April 13). Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://tricare.mil/mtf/WalterReed/About-Us/Our-Rich-History

- West Virginia Pioneers. (2001-2020) Retrieved May 27, 2020, from Bertha Jane Welch, http://www.wvpioneers.com/getperson.php?personID=I106323&tree=WVP

- Why Colonel Ruby Bradley Was Known as the Angel in Fatigues - Medals. (2019, May 31). Identify Medals. https://www.identifymedals.com/article/why-colonel-ruby-bradley-was-known-as-the-angel-in-fatigues/

- Wikipedia. (2020, May 18). United States Army Nurse Corps. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Army_Nurse_Corps

- WVCulture, (n.d) History Education Images. Retrieved May 27, 2020 from http://www.wvculture.org/history/education/images/gilmer/gilmer007.jpg